Popular belief holds it that having a drink can help you to improve your performance in a foreign language — but is this true?

Image Source: iStock ilyabolotov

1) The Connection between Our Fluency and Our Mental State

Is there a strong connection between our fluency and our mental state? Can our mood impact our foreign language speaking ability? It appears so. When we are surrounded by friends in a social setting, discussing current topics in a comfortable environment while having a few drinks, we tend to feel more at ease and confident. By removing the fear of failure, we become more willing to take risks, which leads to quicker learning and improved communication.

2) Positive and Negative Effects of Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol consumption can have both positive and negative effects on language learning and speaking abilities.

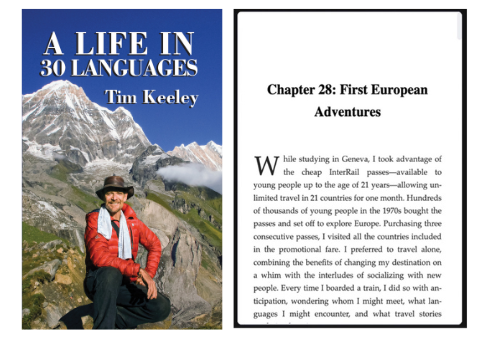

I have had those times when I felt I could communicate much better in a foreign language while drinking beer. I relate one such example in Chapter 28 of my book A Life in 30 Languages. Ironically, the language in question was Dutch and it is said that in the short term, alcohol can reduce inhibitions and anxiety, which may make it easier for some people to speak a foreign language with more confidence; an effect known as “Dutch courage.”

However, this effect is not universal, and some people may find that alcohol actually makes them more nervous or impairs their ability to communicate effectively. Let’s take a closer look at the evidence (some of which also involves Dutch!) since alcohol consumption can also impair cognitive functions, such as memory, attention, and concentration. These functions are crucial for language learning and speaking, so alcohol may make it more difficult for people to recall vocabulary or grammar rules, and to speak accurately and coherently.

3) Low Dose of Alcohol Can Facilitate Fluency

Researchers from the UK and the Netherlands published a study in the Journal of Psychopharmacology which found that a low dose of alcohol could help people speak a foreign language more fluently.

The experiment included 50 native German speakers who had passed a Dutch proficiency exam at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. The participants were split into two groups, with one group receiving water and the other group receiving a low dose of alcohol.

The participants were randomly assigned to drink either a low dose of alcohol or 250 milliliters of chilled water. The dosage for the alcoholic drink was adjusted to each individual’s weight. For a male weighing 70 kilograms, this was equivalent to 460 milliliters of 5 percent-alcohol beer.

They were then asked to hold a casual conversation with an interviewer in Dutch. Recordings of the conversations were rated by two Dutch speakers who didn’t know which participants had consumed alcohol.

The participants also scored their own performances based on how fluently they believed they spoke. Surprisingly, alcohol did not affect the speakers’ self-ratings. Those who drank alcohol were not any more confident or satisfied with their performances than those who had water.

Those who listened to the recordings rated the alcohol group as having better fluency, specifically better pronunciation, than the water group. Ratings for grammar, vocabulary, and argumentation were similar between the groups. However, the authors caution that higher levels of alcohol consumption could have the opposite effect on fluency.

It is unclear whether the participants’ improved speech was due to the biological or psychological effects of alcohol because they knew what they were drinking. Past research suggests that people who believe they are drinking alcohol can experience similar levels of impairment as those who are actually drinking. The authors recommend future research include an alcohol placebo condition to differentiate between the impact of pharmacological and expectancy effects.

Though the study did not include measurements of the participants’ mental states or emotions, the researchers conjecture that a low-to-moderate dose of alcohol may reduce language anxiety and consequently increase proficiency. They conclude that such a result might enable foreign language speakers to speak more fluently in the foreign language after drinking a small amount of alcohol.

4) Related Research

A 1972 study by Guiora and his colleagues also showed that small doses of alcohol improved Americans’ pronunciation of words in Thai. I write about this work in depth in my blog focusing on The Role of Language Ego Permeability in Gaining a Native-like Fluency and Accent in Foreign Languages. (LINK)

A Full Discussion of my experience related to this topic is in Chapter 28 of my memoir. A Life in 30 Languages

References:

Guiora, A. Z., Beit-Hallahmi, B., Brannon, R. C. L., Dull, C. Y., and Scovel, T., (1972) The Effects of Experimentally Induced Changes in Ego States on Pronunciation Ability in a Second Language: An Exploratory Study.

Renner, F., Kersbergen, I., Field, M., and Werthmann, J., (2017)

‘Dutch courage? Effects of acute alcohol consumption on self-ratings and observer ratings of foreign language skills’ from Journal of Psychopharmacology 2018 Jan;32(1):116–122. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29043911