Table of Contents

- Language Learning Can Actually Alter the Structure of the Brain

- Language Learning Promotes Greater Concentration and Cognitive Control

- Language Learning Promotes Cognitive Flexibility and Creativity

- Bilingual Children Tend to Exhibit Faster and Better Development of Linguistic Awareness

- Foreign Language Acquisition is Associated with Good Academic Performance

- Language Learning is Associated with Higher Scores on Tests for Verbal and Nonverbal Intelligence

- Language Learning Promotes Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Development at any Age

- The Cognitive Advantage of Multilingualism Related to the Efficiency and Flexibility in Processing Sound

- Language Learning Promotes Working Memory Improvement

- References

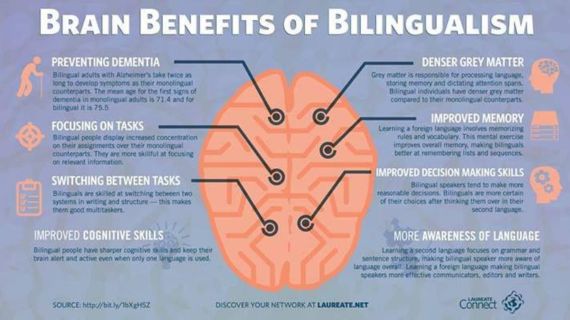

Learning foreign languages offers significant cognitive benefits that are accessible to individuals of all age groups. Research has consistently shown that language learning enhances memory, improves problem-solving skills, boosts cognitive flexibility, and enhances overall brain function. These benefits extend beyond linguistic proficiency and contribute to cognitive abilities in various domains, such as attention, executive functions, and multitasking. Furthermore, language learning has been associated with a delay in age-related cognitive decline and a reduced risk of neurodegenerative disorders. Whether starting early in childhood or embarking on language learning in adulthood, the cognitive advantages are tangible and provide lifelong benefits to individuals willing to explore the world of foreign languages.

Image Source: blog.tcea.org/bilingual-reading-writing/

1) Language Learning Can Actually Alter the Structure of the Brain

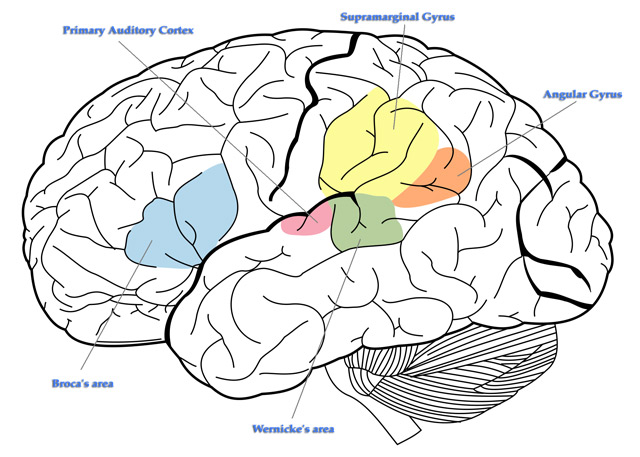

On a fundamental level, language learning can actually alter the structure of the brain. Bilinguals have denser grey matter in their language centers than monolinguals. The parts of the brain devoted to memory, reasoning, and planning can be increased through foreign language acquisition.

A study by Martensson et al. (2012) in Sweden demonstrated growth of language-related brain areas after foreign language learning. They studied cortical thickness and hippocampal volumes of conscript interpreters before and after three months of intensive language studies. The results revealed that becoming fluent in another language can increase cortical thickness (the area responsible for higher brain functions) and hippocampus volume (the part of the brain involved in the formation of long-term memory).

For the study, researchers evaluated two separate groups of recruits enlisted in the Swedish Armed Forces Interpreter Academy. One group had no previous knowledge of a second language but spent 13 months learning to speak languages such as Arabic, Russian, and Dari fluently. The other group of recruits (the control group) continued to keep their minds stimulated through educational lessons but did not attempt to learn a language during the course of the study. Both groups received MRI scans before and after the study began. While the brain structure didn’t change for the control group, the group with individuals who learned to master a foreign language saw changes in the brain as mentioned above.

2) Language Learning Promotes Greater Concentration and Cognitive Control

Bialystok, E., Martin, M. M., & Viswanathan, M. (2005): In a study published in the journal Developmental Science, researchers found that bilingual children demonstrated better performance on tasks involving attention and cognitive control compared to monolingual children. Bilingual children showed enhanced abilities in tasks that required resolving conflicting attentional demands.

Costa, A., Hernández, M., & Sebastián-Gallés, N. (2008): In a study published in the journal Cognition, researchers found that bilingual children outperformed monolingual children in tasks that measured cognitive control abilities. Bilingual children exhibited greater accuracy and speed in tasks requiring conflict resolution and inhibitory control.

Carlson, S. M., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2008): A study published in Developmental Science found that bilingual preschoolers demonstrated better executive function skills, including attention and cognitive control, compared to monolingual preschoolers. Bilingual children showed enhanced abilities in tasks related to inhibitory control and attentional flexibility.

Poarch, G. J., & van Hell, J. G. (2012): In a study published in the journal Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, researchers found that bilingual children exhibited advantages in cognitive control compared to monolingual children. Bilingual children demonstrated better performance on tasks that required attentional flexibility and inhibitory control.

In summary, the research results presented here suggest that bilingual children tend to show enhanced attention and cognitive control abilities compared to their monolingual counterparts. Bilingualism requires constant mental juggling and switching between languages, which may contribute to the development of cognitive control processes.

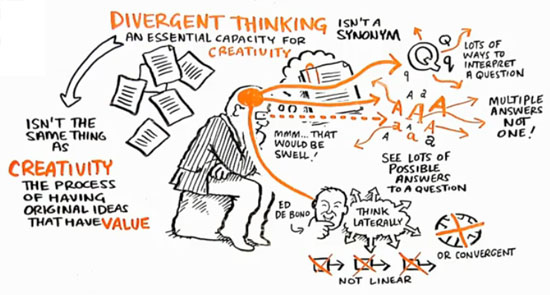

3) Language Learning Promotes Cognitive Flexibility and Creativity

When children are adequately exposed to two languages at an early age, they are more flexible and creative, and they reach higher levels of cognitive development at an earlier age than their monolingual peers. Specifically, they reported that students involved in foreign language learning show greater creativity at solving complex problems than their monolingual peers. Several studies have suggested that language learning promotes cognitive flexibility and creativity. Here are a few examples:

Leung, A. K., & Byrne, R. M. (2008): In a study published in the journal Cognition, researchers found that individuals who were bilingual and learned a second language showed enhanced cognitive flexibility. Bilingual participants demonstrated better performance in tasks that required switching between different sets of rules or categorizations.

Sultan, A. (2016): A study published in the journal Thinking Skills and Creativity examined the relationship between language learning and creativity. The findings indicated that individuals who acquired multiple languages tended to have higher levels of creative thinking compared to monolingual individuals.

Li, P., Legault, J., & Litcofsky, K. A. (2014): In a study published in the journal Applied Psycholinguistics, researchers investigated the impact of language learning on creative thinking. The results showed that individuals who learned a second language exhibited greater creative problem-solving abilities compared to monolingual individuals.

Dunbar, E., & Kung, F. (2016): A study published in the Journal of Creative Behavior explored the relationship between multilingualism and creativity. The findings indicated that multilingual individuals demonstrated higher levels of creative thinking and generated more creative solutions in problem-solving tasks compared to monolingual individuals.

Kharkhurin, A. V. (2010): In a study published in the journal Psychology of Language and Communication, researchers examined the association between language learning and creative potential. The results suggested that multilingualism positively influenced various aspects of creativity, such as fluency, flexibility, and originality of thinking.

Thus, the research points to the conclusion that language learning can have a positive impact on cognitive flexibility and creativity. Learning and using multiple languages require individuals to adapt to different linguistic systems and engage in flexible thinking, which may enhance cognitive abilities related to creativity and problem-solving.

4) Bilingual Children Tend to Exhibit Faster and Better Development of Linguistic Awareness

Understanding the concept of word as a constituent of language is one of the first (and perhaps most significant) aspects of linguistic awareness that children master. The Russian developmental psychologist Vygotsky proposed that bilingual children would be more likely to grasp the notion that words are formal abstractions of language, because they have two labels for things, and therefore could see the arbitrary nature of the relationship between words and their referents. This concept is regarded as a central one in the acquisition of literacy skills.

Several studies have demonstrated that bilingual children tend to exhibit faster and better development of linguistic awareness, including understanding the concept of words as constituents of language. Here are a few examples:

Bialystok, E., Luk, G., Peets, K. F., & Yang, S. (2010): In a study published in the journal Developmental Science, researchers found that bilingual children showed enhanced metalinguistic awareness, including a better understanding of word boundaries and grammatical structure, compared to monolingual children.

Bosch, L., & Ramon-Casas, M. (2014): A study published in the journal International Journal of Bilingualism found that bilingual children demonstrated earlier sensitivity to word boundaries and a more advanced understanding of word structure compared to monolingual children.

Marchman, V. A., Fernald, A., & Hurtado, N. (2010): In a study published in the journal Developmental Science, researchers found that bilingual infants displayed an earlier ability to segment words from fluent speech compared to monolingual infants.

Silva-Corvalán, C. (1994): In a study published in the journal Language Learning, researchers observed that bilingual children demonstrated more advanced awareness of word formation and morphological structure compared to monolingual children.

Taken together, these studies indicate that bilingual children tend to exhibit accelerated development of linguistic awareness, including the understanding of words as building blocks of language. Bilingualism may provide bilingual children with increased exposure to multiple language systems, leading to heightened sensitivity to word boundaries, morphological structure, and grammatical rules.

5) Foreign Language Acquisition is Associated with Good Academic Performance

The cognitive benefits gained from foreign language acquisition are also clearly measured in academic performance in areas not directly related to the study of languages from primary school through university life. A 1994 report on the impact of magnet schools in the Kansas City Public Schools showed that students in the foreign language magnet schools had significantly boosted achievement overall (Eaton, 1994). The report indicated that students who participated in the language magnet’s first kindergarten in 1988 had surpassed national averages in all subjects by the time they reached fifth grade. The foreign language students performed especially well in mathematics suggesting a connection between the cognitive functions involved in these two subjects.

Another example was reported in an editorial in the Vancouver Sun of October 21, 2004, “Province-wide skills tests in British Columbia consistently show that French immersion students outperform their counterparts in the English stream in math, reading, and writing.” Other evidence of foreign language acquisition promoting improved academic performance includes:

Academic Achievement Studies: Several studies have found a positive relationship between foreign language learning and academic performance. For example, a meta-analysis by Vanderplank (2013) examined various research studies and concluded that learning a foreign language had a positive impact on academic achievement, particularly in areas such as literacy, verbal skills, and cognitive abilities.

Cognitive Benefits: Learning a foreign language has been linked to improved cognitive skills, such as memory, problem-solving, and critical thinking, which are transferable to academic settings. These cognitive benefits can contribute to better academic performance across various subjects.

Cultural Understanding: Foreign language acquisition fosters cultural understanding and empathy, which can enhance students’ overall educational experience. This intercultural competence can positively influence academic performance, particularly in subjects that require a global or multicultural perspective.

Enhanced Language Skills: Learning a foreign language can improve overall language skills, including reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Strong language skills are foundational for success in many academic disciplines, such as literature, communication, and social sciences.

Cognitive Flexibility: Foreign language learning requires individuals to switch between different linguistic systems, which enhances cognitive flexibility. This cognitive flexibility can translate into better problem-solving abilities and adaptability in academic contexts.

6) Language Learning is Associated with Higher Scores on Tests for Verbal and Nonverbal Intelligence

Numerous studies show that people who are proficient in at least more than one language outscore monolinguals on tests of verbal and nonverbal intelligence (for example Bruck et al., 1974; Hakuta, 1986; Waterford, 1986). Rosenbusch, (1995) asserts that the length of time students study a foreign language relates directly and positively to higher levels of cognitive and metacognitive processing.

Here I would like to comment on metacognitive processing, which here should be considered to mean ‘awareness or analysis of one’s own learning or thinking process.’ There is a world of difference between my awareness of ‘how’ I learn languages now that I have studied more than 30 languages to various extents compared to when I took learning my first foreign language seriously, Spanish, at the age of 18 before leaving for Colombia to study at a university there. This has allowed me to become a more independent learner in terms of self-directed learning, and not just in terms of foreign language acquisition. The metacognitive skills I have developed in the process of foreign language learning help me become of aware of the flaws and gaps in my thinking, articulate my thought processes, and revise my learning efforts no matter what the subject is.

7) Language Learning Promotes Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Development at any Age

The brain has much more plasticity than many people realize, and that fact has important implications for adult foreign language learning. Studies have demonstrated that the human brain can and does grow new cells in the hippocampus and that the brain is capable of building virtually an infinite number of neural connections that strengthen the modularities found within the brain. With appropriate stimulation, cortical pyramidal cells grow by adding dendrites that branch and rebranch.

Enriched experiences, such as becoming fluent in a foreign language, enhance neural growth and thus learning. Environmental enrichment changes our neural network patterns or ‘maps of meaning.’ The act of learning a new language can be one of the most potent stimulating experiences that can have a significant impact on continued cognitive development at any age. Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to change and adapt in response to experiences and learning. Language learning involves acquiring new vocabulary, grammar rules, and pronunciation, which can lead to structural and functional changes in the brain and has been associated with increased neural plasticity, meaning the brain’s ability to change and adapt. This can result in enhanced cognitive abilities and intellectual performance.

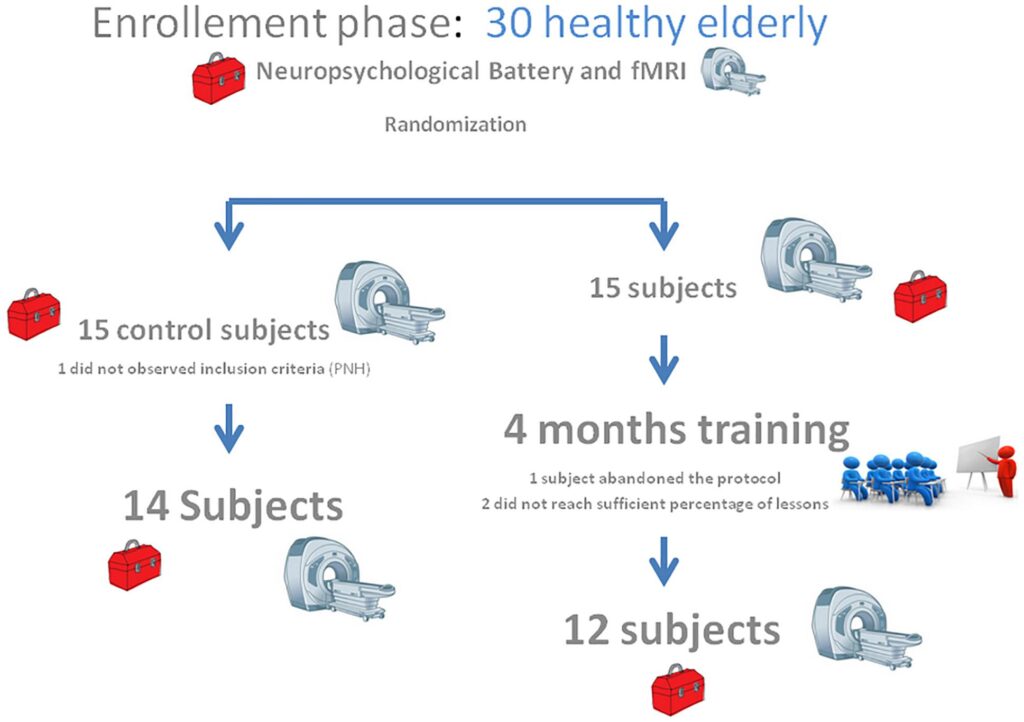

Studies have shown that even in adulthood, language learning can stimulate neuroplasticity and promote the growth of new neural connections. For example, a study by Mechelli et al. (2004) used MRI scans to demonstrate structural changes in the brains of adult learners after a period of intensive language learning. Furthermore, Studies by Stein et al. (2014) and Schlegel et al. (2012) demonstrated that language learning can lead to structural and functional changes in the brain associated with improved cognitive performance. Cognitive Development: Language learning requires various cognitive processes, including attention, memory, and problem-solving. Engaging in language learning activities can strengthen these cognitive abilities and lead to overall cognitive development. Research by Antoniou, Gunasekera, and Wong (2013) found that adult language learners showed improved working memory and executive functions as a result of their language learning efforts.

Delayed Cognitive Decline: Language learning has been linked to potential cognitive benefits in older adults. Research suggests that learning and using a second language can delay the onset of age-related cognitive decline, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. A study by Alladi et al. (2013) found that bilingual older adults developed dementia symptoms an average of 4.5 years later than monolingual individuals.

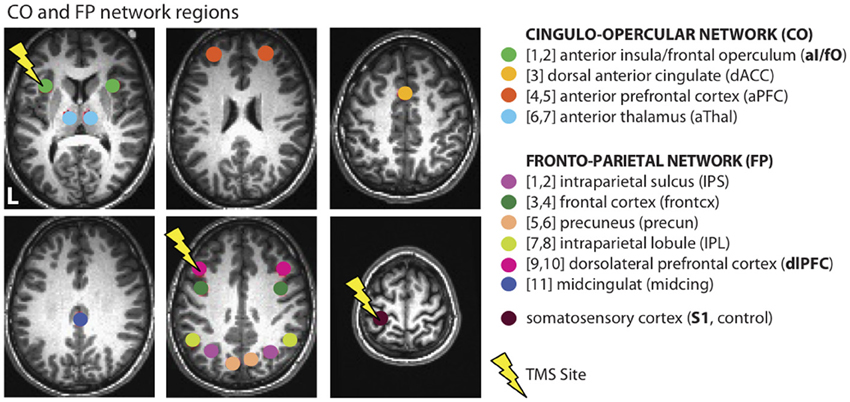

8) The Cognitive Advantage of Multilingualism Related to the Efficiency and Flexibility in Processing Sound

Another cognitive advantage of multilingualism relates to the efficiency and flexibility in processing sound, especially in novel listening conditions. Krizman et al. (2012) experimentally demonstrated that subcortical encoding of sound is enhanced in bilinguals and related to executive function advantages. The researchers examined the subcortical auditory regions of twenty-three bilingual English- and Spanish-speaking teenagers and twenty-five English-speaking teens. To inspect how bilingualism affects the subjects’ brain, they recorded brainstem responses as they heard speech sounds in a silent and noisy setting.

The monolingual and bilingual subjects responded similarly in the quiet condition. However, against a backdrop of background noise, the bilingual brains were better at encoding the fundamental frequency of speech sounds known to underlie pitch perception and grouping of auditory objects, indicating improvements in auditory attention and working memory. The implication is that bilingualism yields functional and structural changes in cortical regions of the brain dedicated to language processing and executive function. Acquiring the ability to function in additional language can increase efficiency in processing auditory information and the executive function of paying greater attention to relevant versus irrelevant sounds.

9) Language Learning Promotes Working Memory Improvement

There have been several studies that provide evidence of the positive impact of language learning on working memory improvement. Here are a few examples:

Antoniou, M., Gunasekera, G. M., & Wong, P. C. (2013): A study published in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews examined the effects of foreign language training on cognitive decline in older adults. The findings suggested that language learning can serve as cognitive therapy and lead to improvements in working memory.

Bartolotti, J., Marian, V., Schroeder, S. R., & Shook, A. (2011): In a study published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, researchers investigated the relationship between bilingualism and working memory capacity. The results indicated that bilingual individuals had enhanced working memory abilities compared to monolingual individuals.

Morales, J., Calvo, A., & Bialystok, E. (2013): A study published in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology examined the effects of bilingualism on working memory in children. The findings demonstrated that bilingual children outperformed monolingual children in working memory tasks.

Barac, R., & Bialystok, E. (2012): In a study published in Developmental Science, researchers found that bilingual children demonstrated superior working memory skills compared to monolingual children. The study suggested that bilingualism can positively impact working memory abilities during childhood.

These studies collectively suggest that language learning, particularly bilingualism, is associated with improved working memory performance. Bilingual individuals, including both children and adults, tend to exhibit enhanced working memory capacity compared to their monolingual counterparts.

10) References

Alladi, S., Bak, T. H., Duggirala, V., Surampudi, B., Shailaja, M., Shukla, A. K., … & Kaul, S. (2013). Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status. Neurology, 81(22), 1938-1944.

Antoniou, M., Gunasekera, G. M., & Wong, P. C. (2013). Foreign language training as cognitive therapy for age-related cognitive decline: A hypothesis for future research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(10 Pt 2), 2689-2698.

Bialystok, E., Luk, G., Peets, K. F., & Yang, S. (2010). Bilingualism, language proficiency, and learning to read in two writing systems. Developmental Science, 13(4), 622-628.

Bialystok, E., Martin, M. M., & Viswanathan, M. (2005). Bilingualism across the lifespan: The rise and fall of inhibitory control. Developmental Science, 8(2), 89-97.

Bosch, L., & Ramon-Casas, M. (2014). Bilingual language development and disorders in Spanish-English speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism, 18(1), 8-21.

Bruck, M., Lambert, W. E., & Tucker, G. R. (1974). Bilingual schooling through the elementary grades: The St. Lambert project in Canada. Canadian Modern Language Review, 30(4), 447-465.

Carlson, S. M., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2008). Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Developmental Science, 11(2), 282-298.

Costa, A., Hernández, M., & Sebastián-Gallés, N. (2008). Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition, 106(1), 59-86.

Dunbar, E., & Kung, F. (2016). Creativity and multilingualism: The influence of second language use on creative problem-solving. Journal of Creative Behavior, 50(4), 262-275.

Eaton, S. (1994). Money, Choice and Equity in Kansas City. Harvard Project on School Desegregation, Cambridge: Harvard University.

Hakuta, K. (1986). Mirror of language: The debate on bilingualism. Basic Books.

Kharkhurin, A. V. (2010). The role of multilingualism in creativity: A study of trilingual and bilingual college students. Psychology of Language and Communication, 14(3), 97-114.

Krizman, J., Marian, V., Shook, A., Skoe, E. & Kraus, N. (2012). Subcortical encoding of sound in enhanced in bilinguals and relates to executive function advantages. PINAS, 109 (20): 7877-7881.

Leung, A. K., & Byrne, R. M. (2008). Switching bilinguals: Task switching between languages enhances cognitive flexibility. Cognition, 106(2), 992-1001.

Li, P., Legault, J., & Litcofsky, K. A. (2014). Bilingual experience enhances executive functioning in children. Applied Psycholinguistics, 35(05), 971-987.

Marchman, V. A., Fernald, A., & Hurtado, N. (2010). How vocabulary size in two languages relates to efficiency in spoken word recognition by young Spanish-English bilinguals. Developmental Science, 13(6), 959-972.

Martensson, J., Eriksson, J., Bodammer, N. C., Lindgren, M., Johansson, M., Nyberg, L. & Lovden, M. (2012). Growth of language-related brain areas after foreign language learning. Neuroimage, 63 (1): 240-244.

Mechelli, A., Crinon, J. T., Noppeney, U., O’Doherty, J., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R. S. & Price, C. J. (2004). Neurolinguistics: Structure plasticity in the bilingual brain. Nature, 431: 757.

Poarch, G. J., & van Hell, J. G. (2012). Executive functions and inhibitory control in multilingual children: Evidence from second-language learners, bilinguals, and trilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15(02), 400-411.

Rosenbusch, M. (1995). Language learners in the elementary school: Investing in the future. In R. Donato & R. Terry (Eds.), Foreign Language Learning: The Journey of a Lifetime: 1-36. Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook Co.

Schlegel, A., Rudelson, J. J., & Tse, P. U. (2012). White matter structure changes as adults learn a second language. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(8), 1664-1670.

Silva-Corvalán, C. (1994). Language switches in Mexican-American bilinguals: Impact of age of onset and linguistic dominance. Language Learning, 44(4), 527-551.

Sultan, A. (2016). Language learning and creativity: A systematic review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 21, 230-244.

Vanderplank, R. (2013). The impact of learning a second language: A review for adult learners. Research Notes, 54, 12-25.

Waterford, M. E. (1986). Bilingualism and performance on nonlinguistic cognitive tests. In S. S. Gillis (Ed.), The development of second language proficiency (pp. 131-146). Cambridge University Press.

Reference:

Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism (3rd ed.). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.