Table of Contents

- No Genealogical Relationships

- The East Asian Cultural Sphere

- The Japanese Writing System

- The Korean Writing System

- The Vietnamese Writing System

- Shared Sino-Vocabulary

- Middle Chinese phonology in Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese

- Wasei-kango (和製漢語)—Character Words Made in Japan

- Grammatical Similarities between Korean and Japanese

- Honorifics in Korean and Japanese

- Japanese, Korean, and Chinese are “Head-Last” Languages

- Conclusion

Welcome to my blog post on the fascinating relationship between Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese languages. Although these languages do not share direct genealogical relationships, their geographical proximity and historical interactions have resulted in significant cultural and historical influences. In this article, we will explore how learning one of these languages can enhance your ability to learn the others. From shared vocabulary and writing systems to grammatical similarities and cultural context, we will unravel the fascinating connections that exist among these languages. Join us on this linguistic journey as we uncover the advantages of multilingualism within the Kanji Bunka Ken and delve into the intricacies of language learning across this diverse linguistic landscape.

Image Source: Tudip Digital

1) No Genealogical Relationships

The Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese languages are not directly related in a linguistic family tree sense, like Romance or Germanic languages, but they do share significant cultural and historical influences due to their geographical proximity and historical interactions.

Chinese, specifically Mandarin, is part of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Vietnamese is part of the Austroasiatic language family, which also includes Khmer in Cambodia and several languages in India. Korean is considered a language isolate, meaning it doesn’t have a clear relationship to any other language, though some theories suggest a possible link to the Altaic language family. Japanese is part of the Japonic language family, which includes Japanese and the Ryukyuan languages spoken in the Ryukyu Islands, south of the Japanese mainland.

2) The East Asian Cultural Sphere

The East Asian Cultural Sphere, also known as the Sinosphere or the Kanji Bunka Ken, refers to the countries and regions that were historically influenced by the culture of China. The sphere includes countries like Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and sometimes extends to include other regions like Singapore and Malaysia. The term “Kanji Bunka Ken” specifically refers to the spread and influence of Chinese characters (Kanji in Japanese) in these regions.

Chinese civilization and culture had a profound influence on these neighboring countries, impacting their writing systems, literature, art, philosophy, political structures, architecture, and more. The Confucian and Buddhist philosophies, in particular, had a significant impact across the region.

Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese languages and cultures were greatly influenced by China. The logographic script of the Classical Chinese language—Chinese characters—became an early regional lingua franca in the written form and, as such, was a significant facilitator of cultural exchange throughout the region.

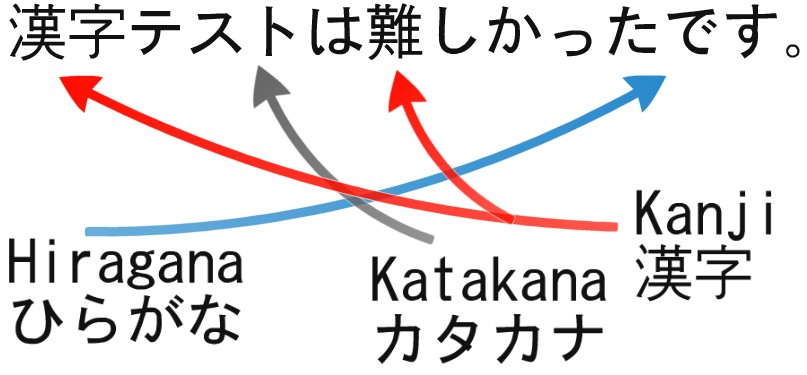

3) The Japanese Writing System

The Japanese writing system is unique and complex, consisting of three main scripts: Kanji, Hiragana, and Katakana. Each script has a different origin and use.

Kanji: Kanji are logographic characters borrowed from the Chinese writing system. The adoption of Kanji began as early as the 5th century AD when Japan had significant cultural contact with the Chinese mainland. Initially, the Chinese characters were used to write Japanese words with the same or similar meanings. Later, they were also adapted to represent Japanese words phonetically. There are thousands of Kanji characters, each representing a concept, a word, or a syllable, and each can have multiple readings based on the context.

Hiragana: In the Heian period (794–1185), a script called Man’yōgana, which used Chinese characters phonetically, evolved into a simpler script known as Hiragana. Hiragana is a syllabic script and is used to write native Japanese words not covered by Kanji, grammatical particles, and word endings. It’s also often used in children’s books or for learners of the Japanese language because it represents all sounds in the Japanese language.

Katakana: Katakana, also a syllabic script, was developed by Buddhist monks in the Heian period as a shorthand for Chinese characters. It is used primarily to write foreign words and names, onomatopoeic expressions, technical and scientific terms, and for stylistic purposes, such as emphasis or to represent telegrams or headlines.

In the 20th century, the Japanese government standardized the use of Kanji and established the Jōyō Kanji, a list of characters to be taught in schools and used in official publications. The list currently contains 2,136 characters.

The modern Japanese writing system is a combination of these three scripts. A typical sentence will often contain all three, with each script serving its specific function. This unique combination allows for a high degree of precision and expressiveness in written Japanese.

The number of Kanji characters you need to know to read Japanese depends on the level of proficiency you’re aiming for.

In Japanese elementary or primary school, students are taught 1,006 basic Kanji characters, known as the Kyōiku Kanji, across the six years of elementary education. These characters cover many of the most common concepts and are a good starting point for reading simpler texts or children’s books.

For more advanced reading, such as newspapers and literature, knowledge of the Jōyō Kanji is required. Beyond the Jōyō Kanji, there is the Jinmeiyō Kanji, a list of additional 863 characters used in names. Some of these characters also appear in literature and specialized texts.

Keep in mind that these are guidelines for literacy and that the total number of Kanji, including those not in common use, is much larger. However, with the Jōyō Kanji and a solid understanding of Hiragana and Katakana, you should be able to read the majority of Japanese texts

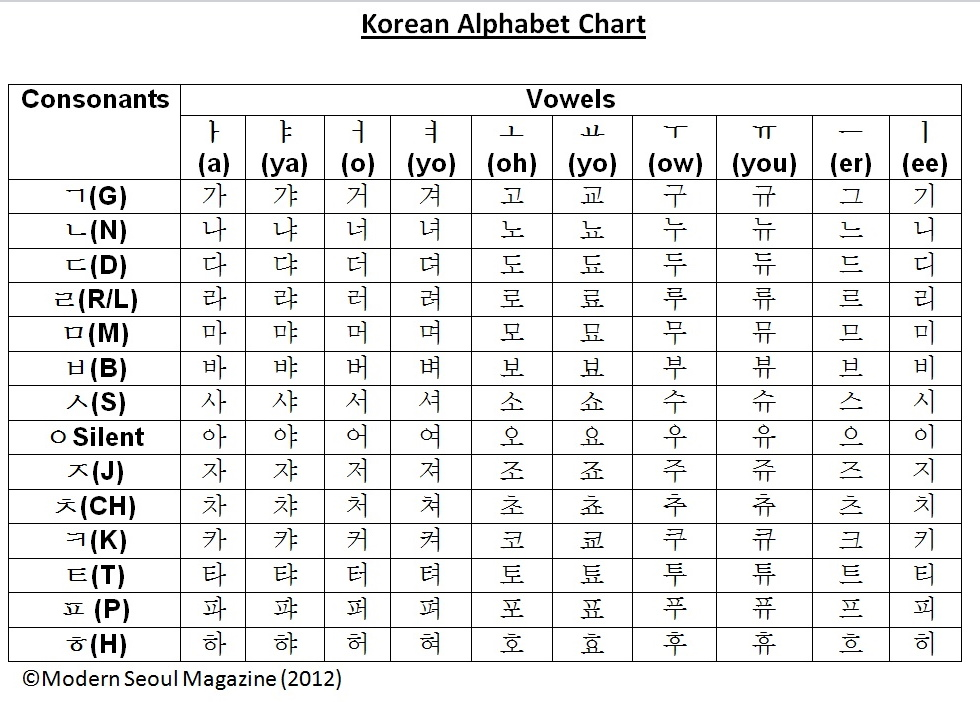

4) The Korean Writing System

The Korean language has a unique and fascinating writing history. Before the invention of Hangul, the current writing system, Chinese characters were used extensively in Korean writing. This period of using Chinese characters is typically divided into two stages: Classical Chinese and Hyangchal.

Classical Chinese: For many centuries, the Korean elite used Classical Chinese for official documents and literature. This was due to the significant cultural influence of China over East Asia. However, Classical Chinese was difficult for the common people to learn and understand due to its complexity and the lack of correlation between the Chinese and Korean languages.

Hyangchal and Idu: These were systems that used Chinese characters to write Korean. In Hyangchal, Chinese characters were used to represent Korean words phonetically, much like how Katakana is used in Japanese. Idu was a similar system used more officially, with Chinese characters representing both meaning and sound.

Despite these systems, the use of Chinese characters created a significant barrier to literacy because of the difficulty and time-consuming nature of learning thousands of characters.

Hangul: In 1446, King Sejong introduced Hangul to promote literacy among the common people, who often did not have the education or resources to learn the complicated Chinese characters.

Hangul is a phonetic alphabet consisting of 14 basic consonants and 10 basic vowels. Syllables are formed by combining these consonants and vowels into blocks. The design of the Hangul characters is unique in that the shapes of the consonants are said to mimic the shapes of the speech organs when producing those sounds.

Initially, Hangul faced resistance from the yangban (scholar-official class), who saw it as a threat to their status. However, over time, Hangul’s use spread, especially among women and commoners. In the 20th century, especially after Korean independence in 1945, Hangul became the primary writing system in both North and South Korea.

Today, Hangul is used almost exclusively in everyday life in Korea. Chinese characters, or Hanja, are still used in certain contexts, such as academic papers, historical texts, and sometimes in newspapers for disambiguation. However, their use has significantly declined, and most Koreans only learn a limited number of Hanja in school.

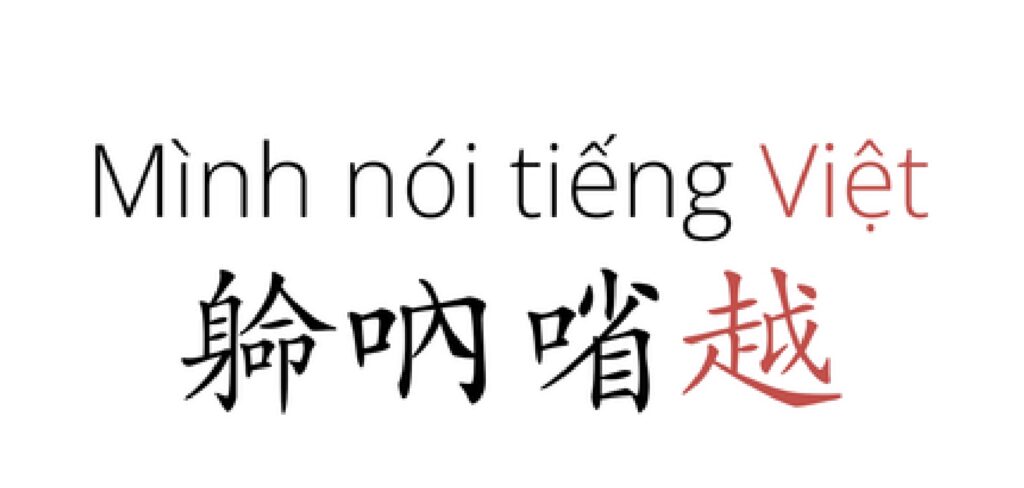

5) The Vietnamese Writing System

In the case of Vietnam, since the beginning of the Chinese rule in 111 BC, literature, government papers, scholarly works, and religious scripture were all written in classical Chinese (Chữ Hán).

Early Vietnamese Scripts: Before the 13th century, Vietnamese used a writing system based on Chinese characters called Chữ-nho or “Confucian script”. This system, similar to Hanja in Korea, was primarily used by scholars and the elite. It was not readily accessible to the common people due to the complexity and vast number of characters.

Subsequently, the Vietnamese used Chữ Nôm—a writing system based on Chinese characters—from the 13th century to the 19th century. This system was a unique attempt to create a native script using modified Chinese characters. Some characters were used for their meaning, while others were used phonetically. While Chữ Nôm was a significant step towards a distinct Vietnamese script, it was still complicated and not widely accessible to the average person.

Latin-based Script (Chữ Quốc Ngữ): The most transformative change in the Vietnamese writing system came in the 17th century with the arrival of Portuguese and French missionaries. These missionaries developed a Latin-based script to transcribe Vietnamese sounds, which is known as Chữ Quốc Ngữ or “national language script”.

This script added diacritical marks to indicate tones, a critical feature of the Vietnamese language. After that, the French Catholic missionary Alexander de Rhodes revised the Romanized writing system still in use today—Quốc ngữ.

Initially, this new script was mainly used by the Christian community. However, during French colonial rule in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the French administration promoted the use of Chữ Quốc Ngữ and began to phase out Chữ Nôm. By the early 20th century, Chữ Quốc Ngữ had become the standard writing system for Vietnamese.

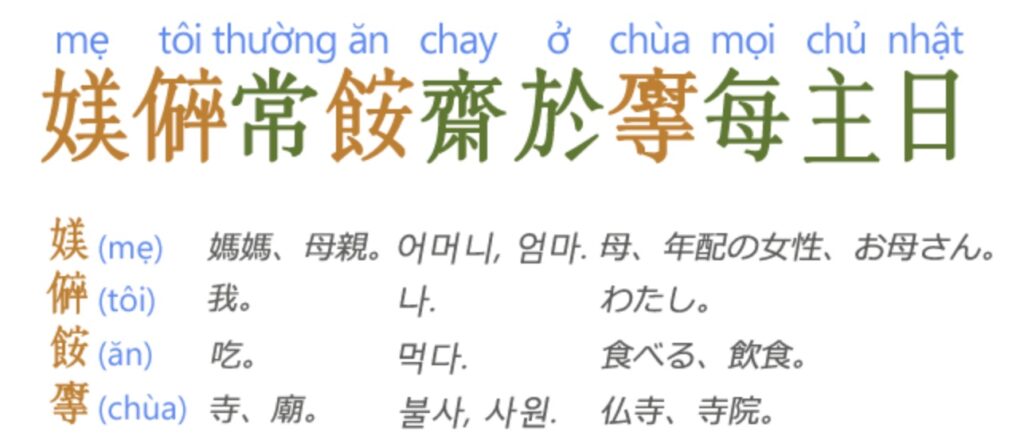

6) Shared Sino-Vocabulary

The influence of Chinese on the Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese languages is indeed substantial, especially in terms of vocabulary. This is primarily due to the long history of cultural and political contact with China.

In Japanese, it’s estimated that around 60% of the words are of Chinese origin, known as kango (漢語). However, in everyday conversation, the proportion of kango is generally lower, as many basic words and grammatical elements are of native Japanese origin.

In Korean, about 60% to 70% of the vocabulary is of Chinese origin, known as hanja-eo (한자어, 漢字語) or Sino-Korean vocabulary. However, just like in Japanese, many everyday words and grammatical elements are native Korean.

In Vietnamese, approximately 60% of the vocabulary has Chinese origins, known as Hán-Việt words. However, most common words and phrases in Vietnamese are native. Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary is a layer of some 3,000 monosyllabic morphemes borrowed from Literary Chinese with consistent pronunciations based on Annamese Middle Chinese.

Most words of French origin relate to objects, food, and technology introduced to the Vietnamese during the colonial era. Many staple foods in Vietnam are French dishes modified to include local ingredients: omelets, baguettes, croissants, and anything fried in butter. Certain ingredients—cauliflower, zucchini, pate, and potatoes—were introduced to Vietnam during the colonial years.

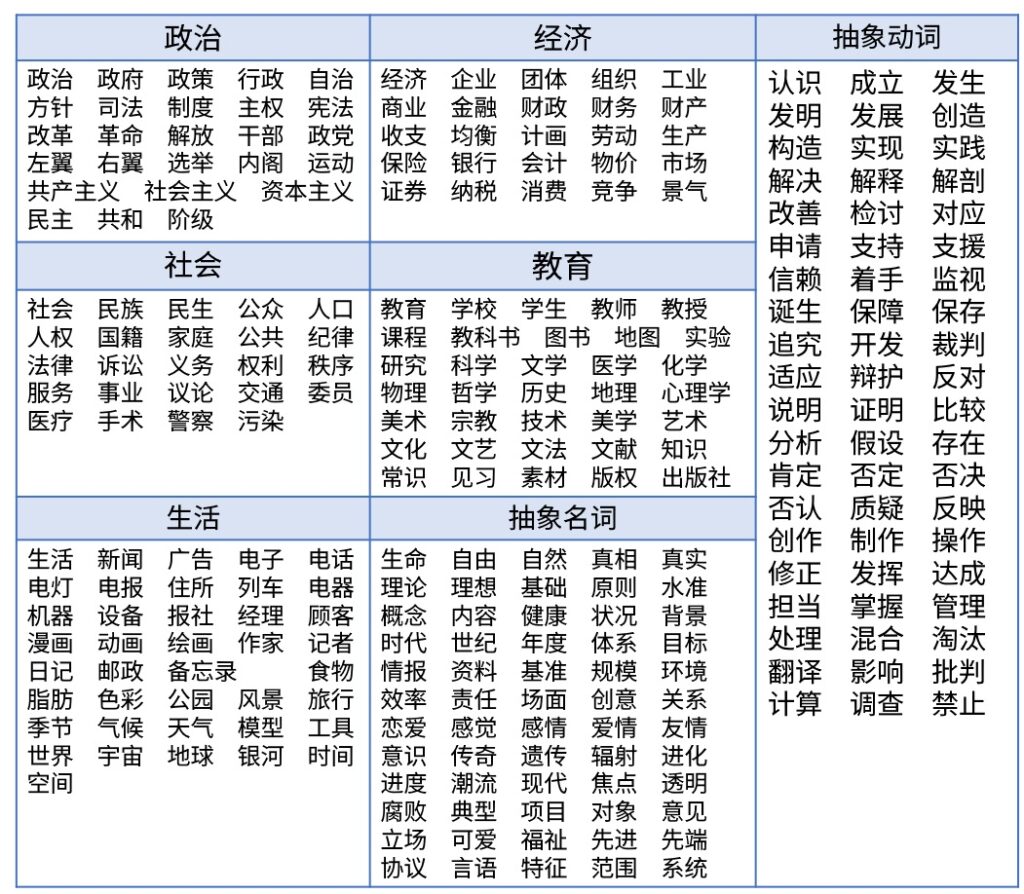

The significant presence of Sino-vocabulary in these languages can help learners who have a background in Chinese, as they may find familiar elements in the vocabulary. Similarly, knowledge in one of these languages can provide a useful foundation for learning the others.

7) Middle Chinese phonology in Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese

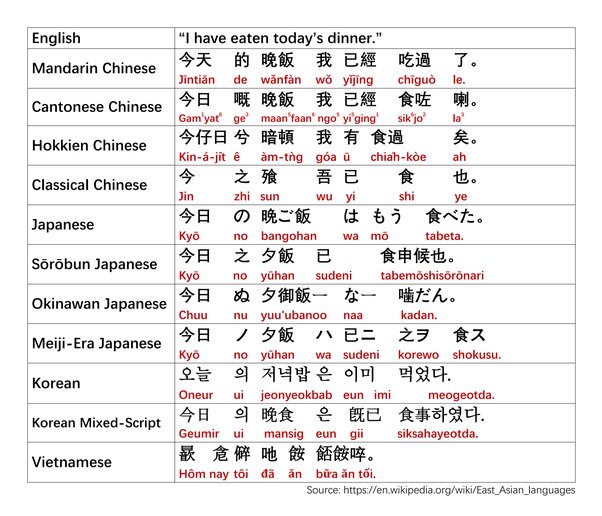

During the Tang dynasty (618–907), Chinese writing, language, and culture were imported comprehensively into Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. Scholars in those countries wrote in Literary Chinese and were thoroughly familiar with the Chinese classics, which they read aloud in systematic local approximations of Middle Chinese.

The phonology of Cantonese, Hakka, and literary Hokkien, as well as the readings of Han characters in Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese all preserve much better correspondence with Middle Chinese phonology than Mandarin. Thus, the pronunciation of Sino-vocabulary in Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese is often more similar to one another than to modern-day standard Chinese.

8) Wasei-kango (和製漢語)—Character Words Made in Japan

“Wasei-kango” (和製漢語) is a term used in Japanese linguistics to refer to words that were created in Japan using Chinese morphemes (kanji characters), but do not exist or originated in Chinese language. The term “wasei-kango” literally translates to “Japanese-made Chinese words”.

These words were often created to express modern concepts or ideas that didn’t exist in the classical Chinese lexicon. Examples of Wasei-kango include 自転車 (jitensha, meaning bicycle), 電話 (denwa, meaning telephone), and 乗り物 (norimono, meaning vehicle).

As for their presence in Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese:

Chinese: A large number of Wasei-kango have found their way into modern Chinese, often without speakers being aware of their origin. One estimate is that 30% of modern Chinese vocabulary is of Wasei-kango origin. This is largely due to cultural exchange and the modernization processes in East Asia where Japan had an early lead. Here are some examples:

煙草 (Yāncǎo in Chinese, Tabako in Japanese) – Both languages use this term for “tobacco”. It was created in Japan and later borrowed into Chinese.

文化 (Wénhuà in Chinese, Bunka in Japanese) – While this term originally existed in Chinese, its modern meaning of “culture” was developed in Japan during the Meiji period and later re-imported back into Chinese.

世界 (Shìjiè in Chinese, Sekai in Japanese) – This term means “world”. It was popularized by Japan and later adopted by Chinese.

主義 (Zhǔyì in Chinese, Shugi in Japanese) – This term means “ism” as in socialism, capitalism, etc. It was first used in this sense in Japan and then borrowed into Chinese.

幹部 (Gànbù in Chinese, Kanbu in Japanese) – This term, meaning “cadre” or “executive”, was coined in Japan and later borrowed into Chinese, where it has become a standard term in political and organizational contexts.

國際 (Guójì in Chinese, Kokusai in Japanese) – This term, meaning “international”, is another example of a word that was popularized in Japan and later adopted by Chinese.

Korean: Many Wasei-kango have made their way into Korean, primarily due to the period of Japanese rule from 1910 to 1945. They were often adopted without the Korean speakers’ awareness of their Japanese origin. After World War II, some of these words were replaced with new Sino-Korean or native Korean terms, but many remain in use.

Vietnamese: Some Wasei-kango have been adopted into Vietnamese, mainly through the influence of kanji-hanja learning and Japanese culture. However, due to the different historical and cultural context, the number of Wasei-kango in Vietnamese is limited compared to Chinese and Korean.

9) Grammatical Similarities between Korean and Japanese

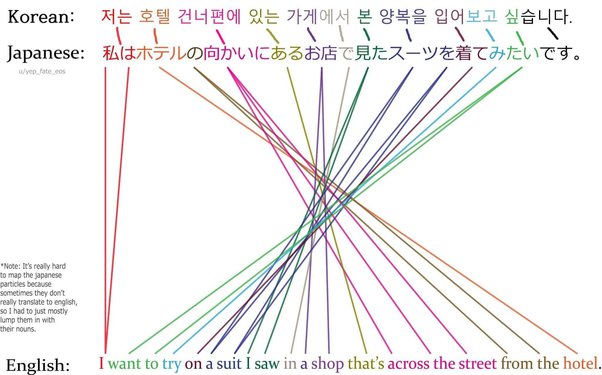

Linguists claim no clear genealogical relationship exists among the Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese languages. However, besides cognates originating from Chinese, Japanese and Korean grammar are at least 90% similar.

SOV (Subject-Object-Verb) Word Order: Both languages follow this word order. For example, the English sentence “I eat apples” would be structured as “I apples eat” in both Japanese and Korean.

Postpositions: Both Japanese and Korean use postpositions (also known as particles), which come after the words they modify. This is unlike English, which uses prepositions that come before the words they modify.

Agglutination: Both languages are agglutinative, meaning that they attach affixes to a root word to express grammatical relations, including tense, mood, and honorifics. They employ analogous grammatical particles for linking the words in a sentence. These characteristics allow words of different parts of speech to be placed in precisely the same order if sentences are translated from one language to another.

Here are a few examples of similar grammatical particles in Japanese and Korean:

Subject Markers: Both languages have particles that mark the subject of a sentence. In Japanese, this is often the particle が (ga), while in Korean, it’s 이 (i) after a consonant or 가 (ga) after a vowel.

Object Markers: Both languages also have particles to mark the object of a verb. In Japanese, this is typically を (wo), and in Korean, it’s 을 (eul) after a consonant or 를 (reul) after a vowel.

Topic Markers: Both languages have particles that indicate the topic of a sentence. In Japanese, this is は (wa), and in Korean, it’s 은 (eun) after a consonant or 는 (neun) after a vowel.

Direction/Location Particles: These particles indicate the direction or location of an action. In Japanese, the particles に (ni) and で (de) often serve these functions, while in Korean, 에 (e) and 에서 (eseo) are used similarly.

10) Honorifics in Korean and Japanese

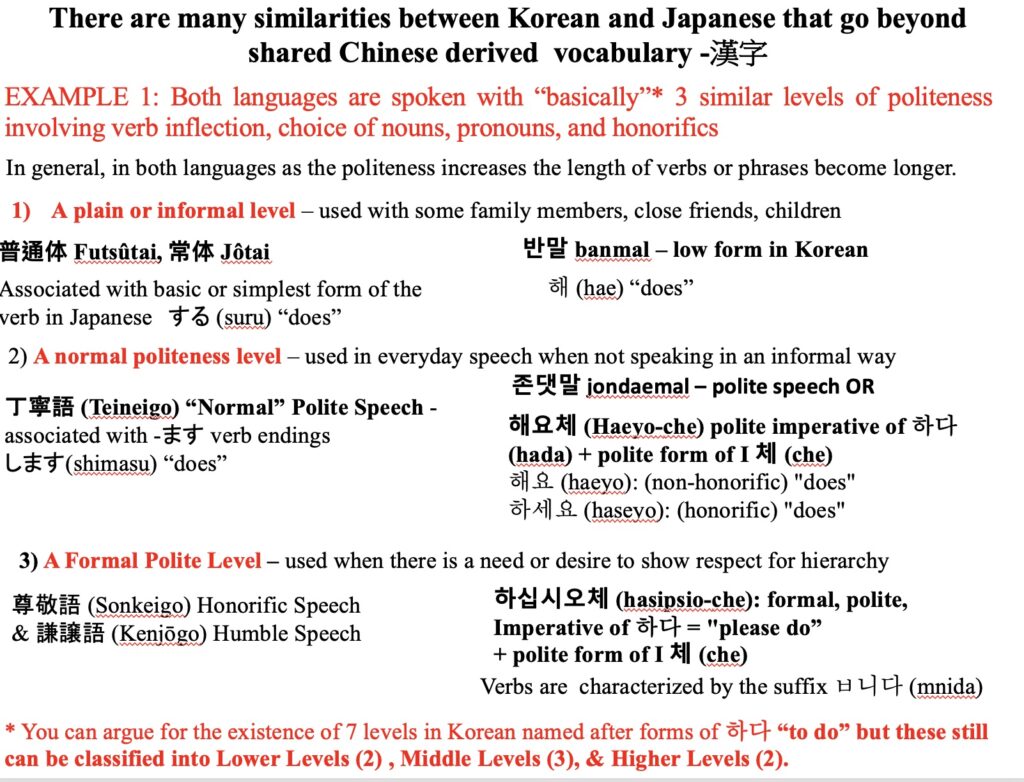

Both Japanese and Korean have complex systems of honorifics that reflect the hierarchical nature of their societies. Honorifics in both languages involve using different words or word forms to show varying levels of politeness, formality, and respect towards the subject of conversation. Here are some similarities:

Levels of Politeness: Both languages have different levels of politeness in speech. In Korean, there are seven levels of speech, though only three (informal low, informal high, and formal high) are commonly used in modern times. Japanese has three main levels of politeness: casual, polite, and honorific.

Respect for Social Hierarchy: Both languages use honorifics to show respect for social hierarchy. This means using different forms of speech when addressing someone of a higher social status, such as an elder, a boss, or a customer.

Honorific Prefixes and Suffixes: Both languages use prefixes or suffixes to make verbs and adjectives honorific. In Japanese, the prefix お (o-) or ご (go-) is added to certain words, and the suffix –ます (-masu) is added to verbs in formal speech. In Korean, the suffix –시 (-si) is added to verbs to show respect.

Honorific Titles: Both languages commonly use honorific titles after a person’s name instead of using “you”. In Korean, titles like 씨 (ssi, equivalent to Mr./Ms.), 선생님 (seonsaengnim, teacher), and others are used. In Japanese, titles like さん (san, equivalent to Mr./Ms.), 先生 (sensei, teacher), and more are used.

Humble and Respectful Forms: Both languages have humble and respectful forms. In Korean, these are known as 하소서체 (hasoseoche, humble speech) and 높임말 (nopimmal, respectful speech). In Japanese, they are known as 謙譲語 (kenjougo, humble speech) and 尊敬語 (sonkeigo, respectful speech).

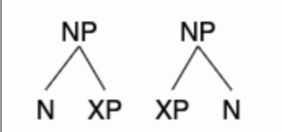

11) Japanese, Korean, and Chinese are “Head-Last” Languages

Some people mistakenly believe that Chinese and English grammar are similar. Chinese basically follows SVO (subject + verb + object) patterns. However, unlike English, Chinese relative clauses precede the noun they modify, like other noun modifiers.

There is usually no relative pronoun in the relative clause. They are considered head-last or head-final languages in the context of relative clauses. In these languages, the noun (or the head) typically comes before the relative clause (or the modifier).

For example, consider the phrase “The book that I am reading”. In these languages, the noun phrase would be constructed more like “I am reading (of) book”:

Japanese: “(私が)読んでいる本” – “(Watashi ga) yonde iru hon”

Korean: “(나는) 읽고 있는 책” – “(Naneun) ilggo issneun chaek”

Chinese: “(我)正在读的书” – “(Wǒ) zhèngzài dú de shū”

This structure often eliminates the need for relative pronouns. For example, in English, you might say “The book that I read was interesting,” with “that” serving as a relative pronoun connecting the main clause “The book was interesting” with the dependent clause “I read (the book).”

In Japanese, the equivalent sentence would be structured as “私が読んだ本は面白かった” (Watashi ga yonda hon wa omoshirokatta), which translates word-for-word to “I read book was interesting.” Korean and Chinese follow a similar pattern.

Korean: “저가 읽은 책은 재미있었다” (Jeoga ilgeun chaeg-eun jaemiisseossda), which translates word-for-word to “I read book was interesting.”

Chinese: “我读的书很有意思” (Wǒ dú de shū hěn yǒuyìsi), which translates word-for-word to “I read book very interesting.”

Vietnamese, like other Southeast Asian languages, is generally classified as a topic-prominent language. This means that the topic of the sentence usually appears first, and the rest of the sentence provides additional information about that topic. This is true for many East Asian languages as well, including Chinese, Japanese, and Korean.

Vietnamese, like English, generally follows a head-first or head-initial structure in terms of noun phrases. This means that the head noun usually comes before its modifiers. However, unlike English, Vietnamese does not typically use relative pronouns.

For instance, in the English phrase “a red car”, the noun “car” (head) precedes its modifier “red”. The Vietnamese equivalent is “xe hơi đỏ”, where “xe hơi” means “car” (head) and “đỏ” means “red” (modifier).

When it comes to relative clauses, however, Vietnamese places the relative clause after the noun, without the use of a relative pronoun. This can be seen in the example “Cuốn sách tôi đọc thú vị” (“The book I read is interesting”), where “tôi đọc” (“I read”) is a post-nominal relative clause modifying “cuốn sách” (“the book”).

12) Conclusion

Studying the four major languages of the Kanji Bunka Ken—Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese— can provide certain synergies and facilitate the learning process. Learning one can help with learning the others due to shared linguistic and cultural features. Here are some examples of why this is the case:

Shared Vocabulary: Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese all have a significant amount of vocabulary borrowed from Classical Chinese. This is especially true in academic, literary, or formal contexts. For instance, the word for “university” is “đại học” in Vietnamese, “daehak” in Korean, “daigaku” in Japanese, and “dàxué” in Mandarin Chinese. All four are derived from the same Classical Chinese term. So, learning one language can help you recognize and understand similar terms in the others.

Shared Writing Systems: Chinese characters, or kanji, are used in both Chinese and Japanese writing, and were historically used in Korean and Vietnamese as well. Even though Korean now primarily uses the Hangul alphabet and Vietnamese uses a Latin-based script, both languages still feature Chinese characters in certain contexts, such as historical texts, academic writing, place names, and personal names. Knowing the meanings and pronunciations of these characters can provide a basis for understanding vocabulary across all four languages.

Grammatical Similarities: While there are significant differences in the grammar of these four languages, there are also some similarities, especially between Japanese and Korean. Both languages use postpositions (particles that come after the noun) and have similar sentence structures, with the verb typically coming at the end of the sentence. This means that understanding the grammar of one can give you a head start in learning the other.

Cultural context: The East Asian Cultural Sphere (Kanji Bunka Ken) encompasses a shared cultural heritage among these countries, influenced by Confucianism, Buddhism, and other aspects of Chinese civilization. Understanding the cultural context of one country can provide insights into the others, helping you make connections between language and culture.

Phonetic Similarities: Many words borrowed from Chinese into Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese retain similar pronunciations, despite the many centuries and changes in each language. This can make it easier to remember and recognize these words across the different languages.

Shared idiomatic expressions and proverbs: Due to historical and cultural connections, many idiomatic expressions and proverbs have been borrowed and adapted across these languages. Recognizing these expressions in one language can help you understand and remember them in another.

Reference:

Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism (3rd ed.). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.